Unfinished Business

When we left Pinedale, Wyoming on August 25th, we left behind a gap. The point where we left the trail was within the evacuation zone for the Dollar Lake Fire, which we wouldn’t be allowed to enter again. Instead, we returned to the official trail by hiking an extra eleven miles from Elkhart Park up to the CDT about fifty miles south of where we’d left it.

We didn’t like the gap. Specifically, we didn’t like that the fire had forced us to break our self-imposed rules for hiking the CDT. We wanted to form a continuous path of footsteps from the Canadian border to the Mexican border (we call this “connecting footsteps”). This rule is hardly universal for thru-hikers. Many hikers will hitchhike past roadwalks or sections of trail. Some hikers have rules about which direction they hike or only hiking the official trail (vs taking alternate routes). We understand that this is all a little ridiculous. But it’s ALL a little ridiculous, you know? And the gap just bothered us. As soon as we created the gap, we began plotting to close it.

After celebrating our completion of the CDT at the Mexican border, we began researching alternate route options and looking into Pinedale’s weather over the previous weeks. It was November in Wyoming, so it was by no means guaranteed that the trail up north would still be passable on foot. We asked some locals about trail conditions and checked with the local Forest Service office. Everyone told us the same thing: there’s not much snow, and the trail should be just fine as long as you come before the next storm. It hadn’t snowed in several weeks, so with snow incoming the following weekend, we packed up the car to head north right away.

We contacted some CDT trail angels based out of Pinedale who’d helped us out earlier in the trail, a couple called Irish and ReRun. Most people would probably have raised an eyebrow at our itinerary, but these are thru-hikers! They enthusiastically agreed to help us finish off our last miles of the CDT. We left our Subaru at their house on Friday, and they dropped us off at Elkhart Park shortly after noon. It was chilly and overcast, but dry at the trailhead. We headed off into the afternoon hoping to make it about nine miles that evening before making camp.

The trail was easier to follow on our first day, where we could see the log cuts and clear path through the trees.

We found the snow pretty quickly, but the trail had been packed down by other hikers heading up to a north-facing viewpoint called Photographer’s Point. The last time we’d been there, the smoke had been so thick that we could barely tell that the Wind River mountains were spread out before us. This time, low clouds settled over the peaks, but we could see the base of the range.

After the popular viewpoint, the snow was deeper and the hiking slower than we expected. There were fewer footprints ahead of us, then none. Toward evening, we began to encounter snowdrifts up to our knees in the deep valleys heading up toward the CDT, but just as night was falling, we found a beautiful patch of dry pine needles to pitch our tent. We pulled off our cold, wet socks and dove immediately into our bags. We’d only made it about seven miles.

In retrospect, this is probably the point at which we should have cut our losses and turned around. We were still hopeful that once we climbed out of the deep, shady valleys and onto sun-exposed rocks, we’d have some clearer trail. We only had one high point to get up and over, then most of our route would be well below the snowline. So, on Saturday morning, we woke up once again in the dark, donned our thick, waterproof socks, and set off into the snow.

Looking north toward Lester Pass shortly after rejoining the official CDT.

Molly is deep in the pain cave as we dig deep to make as much progress as we can on a demoralizing day. If only we had brought some flotation (backcountry skis or snowshoes) with us. Alas.

We realized pretty quickly that it would be a very long day. Without snowshoes or skis, our feet were constantly under a foot of snow. Though the outside temperature was comfortable, our poor toes were freezing in spite of the waterproof socks. We stopped to add another pair of socks underneath and pulled out the toe warmers we’d brought along for this scenario. Except they were duds. We tried another pair. Duds as well.

We reached the CDT mid-morning, hiking about one mile per hour, each step punching through a crust of wind-affected snow into unconsolidated powder up to our knees. We’d planned to hike about 22 miles that day, but we knew by this point that we’d never make it that far by nightfall. We passed a series of frozen lakes and eventually threw on micro-spikes to walk directly on the ice, staying near the edges where the ice was thickest.

Molly hikes along the edge of Little Seneca Lake.

In spite of the immense challenge that this adventure posed, we had to admit that it was still a stunning landscape to traverse.

Onward and upward, we fought our way forward. The trail was completely invisible under the snow and every once in a while, one of our feet would plunge down into the icy water of a creek, still flowing underneath. We were completely alone up there in that frozen landscape, though we followed many sets of moose tracks and saw a black bear, galloping away across the snow in the distance.

We reached our high point in late afternoon and were dismayed to look down across another vast expanse of open snow. By 5pm, the temperature was dropping rapidly. We’d hiked less than thirteen miles, but we were absolutely exhausted. We looked around for a flattish spot in the snow, and decided we had to make camp, though we were still much higher than we’d planned for. We tamped down the snow, set up the tent and struggled our way out of frozen socks and shoes. Our pants were frozen up to mid-calf, so coated in ice they could stand up on their own. We got into our sleeping bags and sat in the tent for a while trying desperately to warm up our feet. Molly’s toes were so frozen, she wasn’t sure what she’d find when she took off her socks. We put on every layer that wasn’t snow-covered, and she held each foot until it began to thaw.

Molly trudges through knee-deep snow with no sign of a trail anywhere in sight. This adventure was lonely, scary, beautiful, and brutal.

We’d expected to be camping around 8,500ft (and well below the snow line), but found ourselves still near 10,700ft with about 22 miles of trail to the closest trailhead. Though the trail would quickly begin to descend, it wasn’t clear how many more of those miles would be deep under the snow. We messaged Irish and ReRun to update them on our plans – we hoped to make it to the closer trailhead by the next evening before nightfall, if possible.

Navigating in the snow is a challenge in the best of times. It’s tough to tell what you’ll find underfoot, and it’s much harder to read the landscape for clues as to where the trail might lead (down along that creek, up and over this ridge, around this little bump or that larger one). All of this is massively compounded in the dark. Without being able to see the peaks around us, the following morning was a frustrating process of trial and error. We were using two apps to help us stay on route, but that meant checking our phones constantly in the freezing cold air. Molly had opened the last pack of toe warmers to try and get through the coldest part of the day, and mercifully, this last set finally worked.

With each waypoint along the trail, we’d set a new goal. It’s 0.6 miles to the creek. Only two miles to the pass! One more mile until we descend below 10k. Each time we’d hit a goal, we’d find more snow ahead. When one of us got demoralized, the other would step ahead and start breaking trail to give them some reprieve. It went on like this for about seven hours.

More frozen lakes that we walked (mostly) along the edge of. We fully recognize how sketchy this looks. You don’t need a leave a comment letting us know.

Finally, the point where we started descending considerably and began to see an end to our post-holing slog through the snow.

Finally, we began to follow a trench in the snow that we could reliably identify as the trail. Heading downhill without needing to constantly check our direction, our progress became much faster. Eventually, the snow was only at our ankles, then just crunching underfoot. When we reached our last set of switchbacks, where we began to find dry trail, we stopped to take our first real break.

Around 1pm, we reached the valley floor, where we could simply stroll along the Green River. I doubt we’ve ever appreciated a clear trail as much as we did in that moment. But we still had almost 12 miles left to the trailhead, so we put in a podcast, put our heads down, and kept on walking. Across the Green River Lakes, we saw the blackened remnants of the Dollar Lake Fire. When we finally made it to the trailhead around 4:45pm, Irish and ReRun met us with hot cocoa and blankets. It meant so much to have friends who we could count on to give us a safe landing after this last trial of the CDT.

BEAUTIFUL, MAJESTIC, SOLID GROUND. By this point, hiking at a normal pace on hard dirt felt magical.

Closer to the trailhead, we got a stunning view across the Green River Lakes.

Burned remnants of the Dollar Lake Fire, which three months prior threw a big ol’ wrench in our plans for the Wind River Range. It had grown to over twenty thousand acres before being extinguished by an early snowfall.

At a quick glance, the burned forest looks like deciduous trees that have lost their leaves for winter. On closer inspection, these are all charred evergreens, starkly black against the fresh snow.

A key personality trait of the thru-hiker is that we instantly forget all of the trials and tribulations of the trail once we’re warm and dry again. It was gently snowing on the drive back to Pinedale, but we knew without speaking that we’d be back out again the next day. We still had sixteen miles left to connect our footsteps from the Green River Lakes trailhead to the junction of Union Pass Road, where we’d been picked up back in August. We simply could not leave sixteen miles of flat road walking between us and a completed CDT. So the following morning, we headed out for one last day on the trail in four inches of fresh snow.

Our last day on the CDT was unlike any other. It was the first day on trail when we each walked completely alone. Jonathan dropped Molly off at the first road junction and she began walking south toward the Green River Lakes Trailhead. Then Jonathan drove to the trailhead, left the car, and walked back toward her. We high-fived in the middle, then Molly completed her CDT hike back at the trailhead, picked up the car, and drove north to meet Jonathan for his last few steps. As we walked those last few miles, we both felt at peace. It was time to be done, time to head home. We had successfully completed a fully connected footpath from Canada to Mexico along the spine of the Rockies.

A huge golden eagle watched over Molly’s last few miles of trail.

Geothermal activity in the area creates some warm streams with a strong sulfur smell and some surprising colors.

Jonathan completes the final few steps of his CDT journey to create a fully connected footpath from Canada to Mexico.

Thank you so much to all of you for following along on this wild journey of ours! We have truly loved hearing from you (and seeing some of you!) along the way. We’ve come to the end of our trail journal for now, but we’ll post some stats from the trip next week and perhaps some reflections on the trip, now that we’ve had some time to process it. We feel so lucky to have been able to spend this summer exploring the Rocky Mountains, and we are grateful to all of you who helped us make it possible.

The Southern Terminus

Standing outside of the tent, looking down at the lights of Lordsburg – our final resupply stop on the CDT – I am glad that we didn’t get a room in town for the night. We only have a few more nights on the trail and I don’t feel any need to be indoors, though it means foregoing showers for another four days (it has been three already). Out here, it’s quiet. There’s a full moon, and the desert is luminous. We go through our evening routine, the same one we’ve done every night now for almost all of the 143 days on trail. It’s simple. We don’t get distracted or pulled in different directions.

Down there, it looks chaotic. There are so many lights; so many people moving around after dark. It’s not quite 7pm, but we’ve already had dinner, and it’s very nearly bedtime. I feel a glimmer of worry about reintegrating after trail. About being down among those lights. About no longer having just one single purpose. About being unmoored from this one goal: walk south. I breathe in the clean air, finish brushing my teeth, and climb into the tent. My body is settling down for the night. I have slept better on the trail than I have slept in years.

We took our last zero day in Silver City on November 2nd, the day the clocks rolled back for Daylight Saving Time. It didn’t make any sense for us to adjust to an arbitrary change of the clocks, so we simply didn’t. We rolled our own alarms back an hour to keep our schedule aligned with the sun and carried on as if nothing had changed. This meant waking up at 4:15am, making camp each night around 5:30pm, and heading to bed by 7pm for our last week on the trail.

The road walk out of Silver City on highway 180 was tolerable at 5am, but as the morning began to heat up, unfortunately, so did the traffic. After thirteen miles on pavement, we were beyond relieved to turn off onto a dusty dirt road. For the three days between Silver City and Lordsburg, water was, once again, our primary concern. At one tank, we met a hunter who was posted up in a blind waiting for deer to come down for a drink. He shared his tactics for hunting squirrels while we filtered our six liters and didn’t blink at us dunking our CNOC (dirty water bag) into the algae-covered water. The next source was also spring-filled tank, a large, rusty metal half-cylinder full of electric-green water, which thankfully filtered out cold and clear.

Before dropping down to Lordsburg and the low Chihuahuan desert, we had one more gentle climb up to Burro Peak, the last mountain on the CDT. We relished our last few miles in the forest, knowing that shade would be a limited commodity for the rest of our journey. The view from the top was pretty, if perhaps a bit modest by CDT standards. Still, there weren’t a whole lot of views out across the desert in New Mexico, so we appreciated it all the same. Descending from the summit, we found our last water source for the section, a water cache nearly 30 miles north of Lordsburg. There were 10 gallon jugs full of fresh, clean water stashed behind a large juniper tree near a trailhead, along with three twelve-packs of soda, cans of iced tea, and a cooler full of cookies and doughnuts. The trail angels left two buckets for seats, so we sat down and had a proper tea party.

The last fifteen miles into Lordsburg are perhaps the hottest, flattest, sandiest miles on the entire CDT (which we can tell you has a few hot, flat, sandy miles). We started to see new kinds of desert flora: giant Arizona barrel cacti, fuzzy-looking pincushions, and tree-like yucca plants taller than Jonathan. We were thankful to be in southern New Mexico in November, rather than in the spring or summer when temperatures are frequently in the high 90s. Even so late in the year, the sun was intense, and there was nowhere to hide from the heat of the day.

Prickly Pear cacti

Unripe prickly pear fruit

Winterfat

Looking west toward Lordsburg from about 10 miles away

The CDT had to throw at least a little more shenanigans our way before we finished. Here’s Jonathan crawling under a fence next to the highway into Lordsburg on the official CDT.

South of Lordsburg, the trail was thankfully more solid and less sandy. The walking was easy albeit fairly monotonous. We listened to some podcasts during the heat of the day, but in the mornings, we reminisced about our favorite (and least favorite) sections of trail. In this hot, exposed terrain, we cherished these cool, dark mornings when we’d navigate through the spiny forest of cacti and yucca using the reflective trail markers that trailed off far into the distance. While the sunrise put on a spectacular show, we'd argue over the top five views and made a list of the best and worst parts of living on the trail (on the good list: “Seeing so many beautiful sunrises”; on the bad list: “Can never find a comfortable seat”). We slowly began to realize that the trip was really coming to an end.

Reflective CDT trail markers leading us off into the distance as the sun begins to set.

The last rays of sunshine glow on Big Hatchet Peak.

By sunrise, we had already been walking for an hour and a half.

It is hard to capture what it feels like to hike in the desert at night. In the forest, you feel like you’re in a tunnel with only the light from your own headlamp. In the desert, the slightest glow in the sky lets you see the skyline around you.

We’ve seen far more sunrises on the CDT than in the rest of our lives combined.

On the second to last day, we finally met our finishing crew: Full Circle, Free Samples, Toddler Snacks, and The Show. We all camped together that night, laughing at the oddity of meeting new hikers less than fifty miles from the border. The others slept in the next morning, while the two of us carried on toward the monument. Though we’d resupplied ourselves for thousands of miles at this point, somehow, we had not purchased enough snacks in Lordsburg . We were running out of food. This wasn’t exactly dire (we weren’t going to starve out there), but man… we were hungry. We’d rationed out our snacks to make sure we could each have something left for our last day on trail.

On that last day, while we were taking our customary shade break under the only tree for miles around (it literally had a waypoint on our map for “Big Tree”), an ATV pulled up with two hunters. The driver climbed out dressed in a complete head-to-toe camo combat suit and two silver-plated pistols, one on each hip. He introduced himself as Joe and asked if there was anything we needed, “Food? Water?” We both perked up at the mention of additional sustenance, and we told Joe we’d certainly accept some calories if he could spare them. He walked back around to the passenger side of the vehicle and rustled around for a moment. Then, like some sort of tactical Santa Claus, Joe emerged from behind the ATV with a sack full of clementines and an entire 18-inch long pastrami sandwich. We could have cried with joy. Before he left, Joe also handed us each a shooter of Fireball, insisting that we have something to celebrate with at the monument. We graciously accepted, and he drove off into the desert.

Molly and Jonathan cheesin’ with doughnuts from the water cache before Lordsburg.

It’s hard to express how grateful we felt for this prepackaged pastrami sandwich.

The final miles of the CDT slope down gently toward the border. The American side is brushy and overgrown, but just across the fence in Mexico, there’s a massive farm, busy with tractors, barking dogs, and trucks driving back and forth. The border itself is only marked by a standard barbed wire fence. There’s a CDT monument next to the final trail marker, and a small structure with a corrugated metal roof to provide a little shade. For a mile around the terminus, the land recently came under the control of the US Army, causing an uproar in the hiking community (for good reason, in that the absurd order attempted to block international hikers from accessing the monument). In theory, it now requires permits or DOD escorts for entry, but we never saw any signs of Army oversight. The border patrol had been watching us for days at this point, and clearly weren’t concerned.

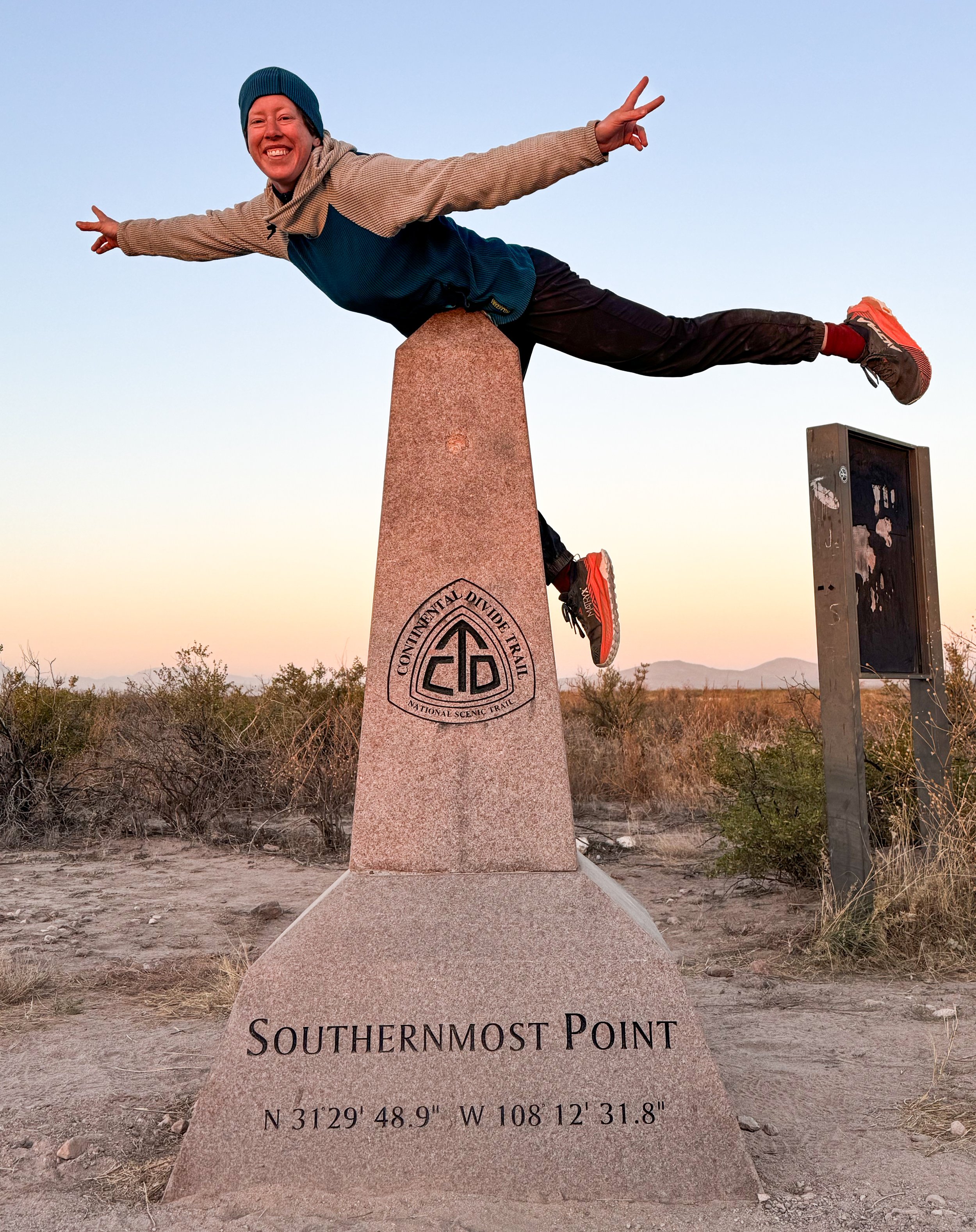

We approached the monument around sunset, and a small plane flew down low overhead, circling around a few times to get a good look at us. Molly threw up a peace sign, then walked up to the monument and burst into tears. We hugged and cried and laughed and danced around the monument. It is theoretically possible that we could have stepped through a rather conveniently-sized gap in the fence to put our feet down in Mexico. We took a few silly photos, then leaned up against the monument to cook dinner and reminisce about everything we’d gone through in the past five months. Then, we set up camp under a dark and gorgeously starry sky.

Molly is still an airplane.

Ride ‘em, cowboy!

The full finishing crew arrived the next morning. There was a dust storm and the sun rose over Mexico in a burnt orange ball. We made a tunnel with our arms for Toddler Snacks and The Show and cheered them to the finish line (then we all did the same for Full Circle and Free Samples, when they showed up an hour later). The shuttle driver, Tim, appeared around 9:30am to take us back to civilization.

Tim is a fascinating person: a retired veteran who has hiked the Florida trail three separate times and who has given thousands of rides to and from the southern border on a donation-only basis. As we drove back down the gnarly, rutted roads, he told us stories about paddling the full length of the Mississippi River. It took about two hours to get back to the highway, then another two hours to Las Cruces where we got a hotel for the night before catching a ride north to Albuquerque with another hiker named Woody and his adorable pup, Mya. We celebrated our finish in the most hiker trash way we could think of. We bought a bottle of prosecco and two bag salads from Walmart. Then, we went back to our hotel room, drank prosecco from plastic water cups, ate our salads straight from the bags, and went to bed before 8pm.

And that, my friends, was that! Or… was it?

Dusty skies at sunrise looking east from the Crazy Cook monument.

Scenes of the Gila

Though it is not on the official trail, the alternate that runs through the Gila Wilderness is regularly voted as one of hikers’ favorite sections of the entire CDT. The trail travels downstream along the Gila River for about 60 miles from the headwaters until the shallow creek becomes a wide, thigh-deep stream.

Though it is not on the official trail, the alternate that runs through the Gila Wilderness (pronounced “hee-luh”) is regularly voted as one of hikers’ favorite sections of the entire CDT. The trail travels downstream along the Gila River for about 60 miles from the headwaters until the shallow creek becomes a wide, thigh-deep stream.

The land surrounding the headwaters of the Gila was the first in the world to be designated as wilderness, which means it has been protected for over 100 years. It is home to the standard array of mountain fauna – deer, elk, coyotes, and bears – but it also boasts javelinas, Mexican gray wolves, and of course, the venomous Gila monster. We didn’t manage to spot any of this majestic wildlife down in the canyon, but we did hear the wolves howling from our tent one night (and successfully confirmed the presence of the rare and remarkable raccoon).

The river cuts a deep path through the high plateau, creating a narrow canyon with cliffs looming hundreds of feet above the water. It was a landscape like none we’d ever experienced. The trail was overgrown and sometimes difficult to follow, but it was nearly impossible to get truly lost. The rock walls often rise up directly from the water on one side of the flow, pushing the trail back and forth from one side of the river to the other. In just three days, we crossed the Gila River around 175 times.

Down in the bottom of the canyon, we only had sunshine for a few hours in the afternoon each day. The mornings were frosty and the water was freezing cold, but as the sunlight started hitting the clifftops above, the valley glowed with a wild, strange beauty. Huge autumn oaks and sycamores with amber leaves flamed as if lit from within while the neighboring banks were still cloaked in deep, cold shade. We found it nearly impossible to capture the feeling of this place in photos; the contrasting light and massive vertical scale made it challenging to fit any part of the scene into a single frame.

Here’s our best effort to bring you along with us into the Gila River valley.

The top of the valley was broad and gently sloping downward. Molly is an airplane.

Deep below the rocky canyon walls, the vegetation was dense and lush.

Sunlight filters through the sycamores. It felt intensely autumnal.

Our early river crossings were shallow and easy.

Where the water pooled against a logjam, scum forms on the stagnant surface, creating this braided texture.

The jigsaw-like texture of the bark on the mountain juniper trees is a fascinating puzzle.

Beanie Baby and Cookie Monster head down toward yet another crossing. We hiked with this pair in Montana, then met up again deep in the Gila valley and spent a morning catching up between river crossings.

Against the base of a narrow tree trunk rests a pile of debris built up from floods that washed sticks and mud through the bottom of the river valley.

As we walked farther down the valley, the river grew wider and deeper.

Jonathan looks up at a cliff hanging steeply over the water. We were frequently forced to one side of the stream or another when the bank disappeared into deeply carved pools beneath the rocks.

Mornings in the valley are intensely cold and the cold persists well into the day, forcing us to keep on our warm jackets while our feet and legs get soaking wet.

This far south, flowers still bloom on the valley floor.

A vibrant, spiny thistle strikes a pose.

Jonathan traverses a beaver dam across the full width of the Gila River in a futile attempt to keep his feet dry for just a few more minutes. Joke’s on him: he’ll never make it through without sticking a foot through the mushy dam into a flowing mess of muddy water.

Molly finds a cascade of wild hops! She reaches out to pick one, and it smells like the freshest IPA.

As we climb out of the Gila River valley, we look back across layers of scrub-covered desert plateaus. After days down on the valley floor, it was easy to forget the hot, dry desert rising high above us.

The Toaster House

I dunno what Pie Town or the Toaster House are, but they have weird names. Let’s dig into some trail culture in rural New Mexico.

Pie Town, New Mexico has a church, a post office, two pie shops, and just about nothing else. There’s a large yellow truck parked on the edge of town that advertises septic services and is cheekily labeled “The Stool Bus”. And just down the road, there’s a very special house.

Our first stop in town was The Gatherin’ Place II, a mighty fine restaurant and pie shop.

The fence and front gate of this house are adorned with a prodigious quantity of toasters (Yes, you read that correctly: toasters. Like, the kind with which you make toast.). Walking through the gate and onto the porch, an entire wall of the house is covered in old hiking shoes, and the chairs are made from the seats of old minivans, which have been pulled out and bolted onto the porch floor. There’s a bike stand in the yard equipped with tools and a pump, but the rest of the yard is cluttered with random art, painted rocks, wood benches, a fire pit, and a rickety old swing set.

Inside, the Toaster House almost looks like a normal family home, because that is how it started its life. There’s a kitchen with a round table, a bathroom, a living room, and a narrow set of stairs to the second floor. Yet, the stairs are coated with stickers. There’s a sign warning you not to use the ancient stove, and a note on the bathroom door suggesting you might consider using the outhouse instead. Upstairs, there are just beds. Beds everywhere! Mattresses on the floor and in every nook and cranny. Another bedroom downstairs has three more beds. The pantry is overflowing with canned soup, peanut butter, and dried pasta. It feels both very lived-in and also simultaneously somewhat abandoned.

A legendary trail angel known as Nita once raised a family in the Toaster House and hosted CDT hikers and GDMBR cyclists. When Nita passed away in 2023, her kids kept the house open to the community, allowing hikers and bikers to continue staying there for free or with a small donation. There’s no sign on the gate, no need to sign in or let someone know you’re coming, no way to know who else might be there at any given time. You simply have to know it’s there and, of course, the hikers know.

In any other part of our lives, the Toaster House would feel ridiculously strange (and possibly rather sketchy). But on trail, it’s another one of those places that make up the foundation of the hiking community. When we arrived at the Toaster House, there were five other hikers milling about. Butter was crafting a friendship bracelet at the kitchen table. Bear Chief was sitting on the slightly rickety-looking balcony and talking on the phone. Samurai was lounging on a mattress upstairs, and Stripes was yard-saled across a neighboring mattress, beginning to pack up his things to head back out on the trail. Wolf was fully packed and saying goodbye as we arrived. The self-appointed caretaker, Carrie, was tidying up the kitchen. Two more hikers showed up while we were there: Burger King and Flavor Town.

We only stayed at the Toaster House for one evening and headed out very early the next morning. But while we were there, we talked with other hikers about past and future adventures, about the best and worst towns on the CDT, about our trashiest hiker moments, and about job searching after trail. We washed our socks, repaired our gear, and drank hot tea. When we woke up at 5:15am, Carrie was already up and about. It was still pitch-black outside, so Molly commented that she was an early riser. “I have church today,” she explained, “so, I have to get ready!” We put on headlamps and walked south down the road out of town. Just another Sunday on the CDT.

The Many Deserts of Central New Mexico

A parental visit and a lot of road walking. Oh yeah, and it turns out that the desert is not a monolith.

Between Ghost Ranch and Pie Town, the CDT alternates between wildly varying desert landscapes and painfully long road walks, Instead of staying high along the divide like the trail through Colorado, the trail through New Mexico only moonlights in the wilderness, then leads directly into each town, requiring long, tedious miles on county roads and state highways. The towns themselves – Cuba and Grants – are full of abandoned motels, boarded up windows, and “Beware of Dog” signs on high metal fences. Just north of Grants, our scenic road tour included a state penitentiary; the highest-rated restaurant in Cuba is a gas station (though the tamales were admittedly exceptional).

New Mexico has a whole lot of this: long, straight dirt roads with miles upon miles of privately owned forest on either side.

Molly’s parents joined us at Ghost Ranch, a guest ranch at the foot of a spectacular box canyon where Georgia O’Keefe lived and painted for a time. The two of them flew to Denver with an entire suitcase of hiker snacks, picked up our Subaru from a friend, and roadtripped down to New Mexico for a ten-day adventure along the trail. Betsey and Charlie helped us out with a lot of trail logistics, offering slackpacks between highways and meeting us in each town with our luxury resupplies (the entire Krumholz family puts a strong emphasis on quality calories – both on and off the trail – so we ate very well through this section). They also squeezed in some adventures of their own, checking out White Sands National Park and Canyon de Chelly National Monument while we hiked through the terrain less accessible from the road. It was really special for us to get this time with them and to introduce them to some of the CDT.

Molly (center) with her parents, Charlie and Betsey

When the trail does venture into the wildness, it’s full of surprises. Just south of Ghost Ranch, the trail climbed through airy, open Ponderosa pine forests into an area that had burned sometime in the recent past. Then, descending into the Chama River Canyon Wilderness, we followed a silty creek. Flash flooding, compounded by burned out roots and bare soil, had washed the trail away completely. Piles of whole trees lay sideways against the few trees still standing on the banks, which had been carved into deep, sandy cliffs. We walked directly in the creek bed, imagining the water rushing fifteen feet overhead in the narrow canyon.

Molly navigates a creek with a washed out bank where brush has been piled up during recent floods.

Slowly, we picked our way downstream, clambering over boulders and branches until we found the trail turning away from the washed-out creek. When we emerged, we found ourselves in another desert landscape, surrounded by cholla cacti and scrubby junipers perched along massive red cliffs soaring above us along the Rio Chama.

The New Mexican landscape is not a monolithic desert, but many unique deserts swirled around each other. One morning, we hiked amongst architectural sandstone formations where spiny crevice lizards flitted under scraggly sage bushes. As we climbed steeply up the side of a wide mesa, we suddenly found ourselves in a low, but dense forest of piñon pine where deer and elk roamed about, and the world’s fanciest squirrels scampered under the trees. Between miles of trail where the highest vegetation barely reached waist-high, the San Pedro Parks Wilderness isn’t a desert at all. Like a tiny Rocky Mountain conifer sanctuary, huge spruce trees are interspersed with broad meadows (the “parks”) with black bears, elk, and meandering streams.

Molly rockhops across a wide, shallow wash.

Dry curls of sand on the desert floor. They make a pleasing crunch when you step on them, like dry leaves in the fall.

Molly perches on an overturned bucket and dunks our dirty water bag into a spring-fed tank. From there, we’ll filter the water into clean bottles.

One of the strangest landscapes of our journey through central New Mexico surrounded Mount Taylor (Tsoodził in Navajo), a now-dormant, 11,305ft stratovolcano that erupted a few million years ago and created massive, barren, black lava flows that extend for miles and miles around the peak. We took an alternate route to the summit and camped high on the grassy slopes, looking out over the lights of Albuquerque to the east. We caught the dawn from just below the summit. It wasn’t until several days later, when we climbed to a low mesa above the highway that we could look back north and see the full extent of the lava fields flowing across the entire valley below.

Dawn from the trail near the summit of Mount Taylor

Looking back toward Mount Taylor, the lava fields of El Malpais National Monument expand into the distance.

By the time we reached Pie Town, our feet were aching from the pavement. The paradox of all that road walking, of course, is that we received more trail magic through this section than anywhere else on the trail. A hiker who’d finished his trip restocked water caches and left sodas stashed along the highways. A construction worker pulled over and reached out of his window to hand us each a 7-Up. Still, we were ready for a long stretch of wilderness and a break from the desert.

A State of Saturation

Maybe it’ll be drier as we leave Colorado and enter New Mexico, our fifth and final state of the CDT. Spoilers: it won’t be drier quite yet.

Leaving Pagosa Springs, our forecast was once again looking a bit grim. The remnants of a West Coast typhoon were blowing across the country, and the area was expecting large amounts of rainfall in a few days’ time. Pagosa Springs and other nearby towns were preparing for widespread flooding. Some forecasts warned that there could be mudslides or flash floods near the trail. We predicted that, if the forecasts were correct, we'd be climbing over 12k feet right as the storm blew in. We were still feeling a little bit raw after the snowstorm in the Weminuche Wilderness so we decided to take a lower route that was similar in mileage, but would get us lower, faster.

The first day out of Pagosa was breezy and cool, but the sun shone for most of the day as we hiked through the Wolf Creek Pass ski area. Then the low route took us down gentle dirt roads through an old mining town called Platoro that's now just a seasonal vacation spot. Nearly everyone had left for the season. There was a slim column of smoke coming from one small house, but the shops were all boarded up for winter. We hiked 32 miles down the road, strolling along, listening to podcasts, and enjoying the sunshine. It stormed and hailed in the afternoon, but only briefly. It was, perhaps, our first hint that we'd made the right decision in taking the low route.

Jonathan cheesin’ at the border between New Mexico and Colorado, which is marked by this elegant monument.

That evening, we camped a quarter mile from the highway to Chama. We met a guy traveling cross-country in a van who played some tunes for us on his guitar as we ate dinner and offered us a ride into town. We explained the arcane rules of our personal game (trying to connect footsteps from Canada to Mexico) and politely declined. Instead, we walked the highway: 13 miles on pavement to get back to the trailhead. (Don't worry. We vetted our friend in the van before divulging our plans: noting a Frank Zappa quote and a tie-dye sticker with the slogan, “Make America Grateful Again”, we determined he was likely harmless.)

A rainbow at dawn as we walked the highway toward Cumbres Pass, where we rejoined the official CDT

At Cumbres Pass, we were lucky enough to catch sight of the steam engine that travels between Chama, NM and Antonito, CO. The railroad was built in 1880.

In Chama, we were safely out of the (really) high country, only three trail miles from the New Mexico border. We'd planned to hike out the same evening to get as far south as possible before the storm struck, but as we stuck out our thumbs, thunder crashed around us and it began to rain in earnest. Panty Pirate walked out from the hotel where he and Steamy were staying for the night and offered to split the room with us. We readily agreed. A warm, dry place to sleep and some great company did, indeed, sound superior to yet another cold, wet night.

In spite of the storm, we caught a ride back to trail just after first light the following morning. It was lightly raining as we left the trailhead, but the weather was merciful as we crossed the border into New Mexico; our last state on the CDT!

Just after the border, the light rain turned into a deluge once again. We walked for five more miles as the trail turned into a river and the temperature began to drop. Our shoes were soaked and our hands were stiff with cold when we decided to call it and make camp until the rain stopped. We looked for a high point to set up the tent, finding a protected spot in the trees on a rise above the trail where we'd be safe from mudslides and flash floods. We set up the tent and cozied into our sleeping bags, peeling off our wet clothes and trying our best to get warm.

We sat in the tent for the rest of the day as it rained and rained and rained. For hours, it pounded on the tent. We listened to an audiobook, ate snacks, and snoozed. Evening came; we never left the tent. All night, it rained off and on. It was still drizzling and gray when we woke up.

It continued to rain off and on over the next couple of days, but off-and-on rain is infinitely easier to manage on the trail. When the sun appears, we can dry out the wet tent. Our jackets dry between outbursts, and our shoes and socks remain only damp (rather than us hydroplaning around in there). Mostly, we walked through a thick, eerie mist.

Days later, we learned that Pagosa Springs had experienced devastating floods as we had been sitting in our tent. While the hiking that day was unpleasant, to say the least, we felt proud of the decision-making that put us in a safe place during the storm. Days of planning, hiking some long days, and choosing a well-placed tent site where water couldn't pool or flood; all of these things put us in a cozy, dry tent rather than on a mountain top (or in a flooded motel room).

Hiking through Colorado in September had been a test of our ability to manage chaotic weather. We felt we'd passed the test, but we had walked south into New Mexico hoping to find a drier, more stable climate. This dripping wet pine forest was not exactly what we had expected to find. Aren't we supposed to be in the desert?! The only thing that seemed vaguely desert-like was the sandy soil, which the rain turned into a thick sludgy paste that stuck to our shoes and wouldn't let go.

Mud coats Molly's shoes, adding weight to every step and rendering the traction worthless.

Around five miles from Ghost Ranch (some 90 miles south of the border), we turned a corner and seemingly walked into a completely different biome. Suddenly, there were cacti everywhere, sandy red cliffs overhead, and the biggest trees were scrubby, ten-foot-tall junipers. A mile further, and we were in a huge box canyon with softly curving walls carved by water and time. A tarantula casually strolled down the middle of the trail (yes, this is the moment where Molly had regrets about going camping in the desert). We followed a dry creekbed down a thousand feet into the canyon, arriving just in time for dinner with some very special guests.

Molly is dwarfed by a field of huge cholla cacti.

Into the San Juans

The daunting San Juan mountain range is the most remote in all of Colorado. Time to get wild, I guess.

The San Juan mountains of southwestern Colorado are some of the highest and most rugged mountains on the CDT. There are thirteen mountains in the range over fourteen thousand feet in elevation and huge swaths of land above ten, eleven, twelve thousand feet. The San Juans are also home to Colorado's largest wilderness area, the Weminuche Wilderness, which covers nearly 500,000 acres. These are some of the wildest, most remote corners of Colorado.

The easternmost 14er in the San Juans is called San Luis Peak. It is not on the official CDT but it's close; the trail runs over a saddle about 1500 feet shy of the summit. The peak is remote and difficult to access without a rugged off-road vehicle (or a whole lot of hiking). The forecast looked great and the night before was cold and clear. We decided to go for it.

Descending from San Luis Peak toward the CDT

There was frost on the grass as we started up the Stewart Creek Trail in the dark. We passed a small cow moose in the weedy creekbed. We'd camped near two other hikers, Ohm Boy and Scurvy. Ohm Boy (named for his pack, the ULA Ohm) passed us on the climb, also heading for the peak. As we reached the first ridge, thick clouds gathered to the west and it was beginning to spit snow. Ah, mountain weather.

When we crested the ridge, the wind was howling and we couldn't see the peak anymore. Onward and upward we climbed. With limited visibility, we were tricked by each new false summit. I could barely see Jonathan, hiking twenty feet behind me. The wind was whipping snow and hail across the trail. By the time we reached the final push, there was an inch of snow on the ground. We could see Ohm Boy's footprints intermingled with a coyote's tracks leading all the way up to the summit. It was slick and rocky, and with the wind in our faces, every step took an enormous effort.

On the summit of San Luis, there is a rock bivvy (a small half circle of rocks built into a wall to give climbers a temporary reprieve from the wind). We clambered inside and sat down for a quick snack, exhausted. Just as we prepared to descend, the wind died down and the clouds parted, drifting away from the peak to reveal stunning views down into the valleys below and out toward the surrounding mountains. Forgetting the freezing, exhausting climb, we gleefully basked in the sunshine and pointed to spiky peaks, aspen-lined hillsides, and the CDT winding away into the distance.

We stayed above 12k feet for most of that afternoon, climbing up to narrow ridgelines and then down the tundra into grassy valleys with huge, craggy peaks above us. As we've come further south, we've noticed the treeline rising. In northern Colorado, treeline falls in the high elevens (11,700 or 11,800 feet), but by the time you reach the San Juans, it has crept upward to the low twelves. As we climbed up onto Snow Mesa, we were still well above the trees.

The view out across Snow Mesa

Walking across the flat top of Snow Mesa, 12,288ft

We walked for three miles across the flat top of the mesa with Uncompagre Peak looming in the distance. At the edge of the mesa, the trail looks like it falls off the edge of the world. It descends down a steep, rocky ravine toward a thick forest of pines and spruce, then aspens glittering in the sunshine and breeze before reaching Spring Creek Pass and the highway to Lake City. Ohm Boy was already at the road, so we stuck out our thumbs and joined him. Our first taste of the San Juans had been a 28 mile day with over 7k feet of vert. We were wiped out but excited for what the rest of the northern San Juans would bring.

We caught a ride to Lake City with a mechanic who plows roads in the winters in Colorado and works on snow cats in Antarctica all summer (for those who may not be familiar, snow cats are large vehicle used for transportation, plowing, and grooming snow). His smelly, but very snuggly mutt cuddled up against me in the truck as we asked him all about his work.

In Lake City — our last stop before entering the Weminuche Wilderness — we stayed at a hostel with a restaurant downstairs and a bakery next door. We met Chew Toy and Side Quest at the hostel and saw some familiar faces at the grocery store: Beanie Baby and Cookie Monster, who we hadn't seen since Montana!

The first two days in the Weminuche were cloudless, breezy, and absolutely stunning. The trail runs through an alpine moonscape; not a tree in sight, herds of elk roaming the tundra, massive, imposing peaks in every direction. The peaks of Vestal Basin rose along the skyline, reminding us of our scrambling trip back in 2022 (I saw Vestal Peak and thought to myself, "Dang, that looks like a gnarly climb!" before realizing that we had, in fact, already climbed it).

Looking back toward Vestal Basin

Sunrise on our second full day in the Weminuche Wilderness

The sun sets over the headwaters of the Rio Grande

On the evening of the second day, clouds began to gather once again. We raced past the Window and the Rio Grande Pyramid as it started to rain. We were safely in our tent by the time the deluge began: rain, hail, thunder, and lightning striking directly overhead. In the dark, we saw Beanie Baby and Cookie Monster hike past in the rain, having come over the pass by the Window as the storm was raging. They later said they'd seen massive trees dropping around them as they sped down the valley, heading for lower ground.

Storm clouds gathering on the horizon

A rainbow over Rio Grande Pyramid, 13,827ft

The setting sun perfectly illuminates the Window during a break in the storm

It rained most of the night, turning to snow just before dawn. We slept in, not excited to hike in thundersnow in the 6am dark. Around 8:30am, we finally left the tent and hiked down the valley as the thunderstorm picked up steam again. At the valley floor, we faced a decision: continue on the red line or bail down to a lower route that could take us into town if needed. The sky was clearing and our forecast was optimistic about the afternoon, so we decided to brave the high country.

It rained a little bit more, off and on. We made it across a broad valley and began to climb again before it started to flurry again. The snow was manageable as we climbed higher, but the temperature was plummeting, and our rain gear was wet from the morning's storm. Once in a while, we caught glimpses of the sun, peeking through the clouds. Then, the snow would begin to blow, and all we could see was white. As we climbed over 12k feet once again, I had to lean against the wind to keep my feet on the trail. I crouched down and marched, poles out wide to support me as my pack created a sail. We pulled our buffs over our faces and powered on.

The snow started to build up. An inch at first, then two, then three. We made it over our first high point, but we were getting colder and colder. Without anywhere to shelter, we couldn't stop to eat or drink. At one point, finding a couple of small krummholz trees to huddle behind, neither of us could work our hands well enough to open a bar, so we bit through the plastic, desperate for a few calories.

Heading up the next rise, less than a mile before we'd descend into lower terrain, I got fully blown off my feet, toppled over by the wind. Jonathan was behind me, walking like a troll to hold his ground. With freezing hands and feet, we decided to put up a bivvy in whatever wind break we could find and focus on just getting warm again. We charged down a valley with no trail and set up the tent in the best shelter we could find.

For two hours, we sat in the tent in our sleeping bags, doing everything we could to get warm. We broke open the emergency hand warmers, ate all the calories we could manage, and held down our little tent, a thin cover of dyneema against gusts of frozen wind. The sun began to creep out around 1pm, as the forecast has predicted, and we emerged from the tent, warm enough to carry on. We climbed through snowdrifts up to our knees, the wind still gusting hard enough to push me off the trail if I wasn't careful.

After the snow storm, the sun began to reappear and we got a glimpse of the changed landscape.

The descent was a quick one. We were eager to get down into the valley where the ridge would provide some wind protection. The trail was muddy as we descended below the snow line, and it stuck to our shoes, so we half-skiied, half-slid down back to safety. At the low point, we found a decent site and set up camp. It was perhaps the hardest fifteen miles I've ever hiked.

Molly descends toward lower ground, relieved to be heading toward a warmer, safer evening.

The next morning, there was not a cloud in the sky. A crust of snow sparkled across our moonscape, now an alpine wonderland. It was cold as we climbed once again into the snow, but we could see the dawn glowing on the horizon. We stopped to bask in the first light of morning, warming our frozen fingers and letting it wash over our faces for a moment. Then, onward! We had a big day ahead: another 28 miles up high with almost 7k feet of elevation gain.

Sunrise glows on the horizon the morning after the snowstorm

Molly traverses the Knife's Edge in snowy conditions. Most of it was completely navigable, but for one short section, we had to kick steps into a steep, snow-covered slope.

As morning turned to afternoon, the snow began to melt rapidly, leaving the trail a slippery, muddy mess. There was often no escape, so we plodded, pleaded, and plowed ahead with a pound of sticky mud coating each sneaker. And yet, the views continued to astound us: ridges covered in tiny spruce trees, wild rock walls, wide alpine lakes, and now and again, a glimpse out toward the low country of New Mexico.

The last morning in the Weminuche held more of the same: beautiful views and terrible mud. We made it to the road just after lunchtime and hitched into Pagosa Springs, directly to a Hmong restaurant with some of the best food we've had on trail. We love you, Colorado. We took the next day off, visiting the free hot springs, drinking real coffee for a change, and our only formidable mountain for the day was made entirely of nachos.

Fall Colors in Central Colorado

This is the good stuff right here! But it’s the CDT, so even “the good stuff” involves some rain, hail, and freezing temps.

After the wild weather of northern Colorado, we headed back to the Front Range for two days at home. Or, kind of at home, anyway. In order to make this trip work financially, we rented out our condo in Boulder with a six month lease. So when our good friend Lexi picked us up from Hessie for a second time, she dropped us off with yet another friend, Kevin, who graciously let us stay for a few nights with him and his golden retriever Phin (14/10 both incredible hosts).

Jonathan, Kevin, Gareth, Molly, Nick, and Yuki (left to right) — a few of the wonderful humans who came to hang out as we passed through the Denver area

In the Front Range, we knocked out some landlord duties, chatted with a few of our awesome neighbors, and Jonathan got a second steroid injection for the plantar fasciitis that has plagued him for the whole trail. We got to see some of the people we love most and worked through a whole lot of trail logistics while getting a little bit of R&R. With only a few shenanigans and an enormous amount of help from Kevin (and snuggles from Phin, of course), we made it back to Berthoud Pass and headed south into central Colorado.

Very sharp teefs

On the first day of the section, we saw eight moose: five bulls, two cows, and a calf! The aspens were radiant and the weather was clear. It's amazing how much a nice day with pretty views can lift our mood. The night was one of the coldest we'd had yet. We woke up with a film of ice inside the tent and our water bottles half frozen. But newly equipped with all of our warmer gear, we were ready for it. Once again, the mountains were reminding us that the seasons were changing.

The weather was slightly better through this section, but the elevation still created some challenges. Camping above 12k feet is cold and exposed. Avoiding it can mean hiking either very short days or very long days with huge amounts of elevation gain. Generally, we've picked the latter. We were hyper-aware of the coming winter, and through this whole section we were pushing ahead to try to get to the San Juans before they became impassable.

The push to get south has meant passing through town without staying overnight. Skipping the shower and laundry to get more miles done once the groceries are in hand is sometimes the more practical decision. In Leadville, we had a good meal, stopped by our friend Andy's house to charge our phones, and received some bonus snuggles from his corgi, Nelson. Andy then dropped us back off on the trail the same evening. We stopped in Twin Lakes just long enough to drink a cup of coffee and pick up some extra snacks. At Monarch Crest, we picked up a resupply box, ate a burrito, and headed up the trail after less than two hours.

Nelson getting a quick snug

It wasn't all just a rush though. The changing colors through this section were unreal. We've never spent so much time in the mountains during this time of year, and it's been an incredible experience to watch the season change at walking speed. Of course, the aspens are eye catching (and I've taken about a million photos of them, because I have to stop and admire each individually). But so many plants are changing colors: whortleberries, gooseberries, mountain roses, and wild strawberries. The whole tundra is turning a deep shade of red. And I've been surprised by the other colors that I don't see when I'm at home: pale yellows, deep maroons, and even delicate lavenders. In the evenings, we hear elk bugling. We see herds of them lower down in the valleys as they begin descending to their winter grounds.

The day before Twin Lakes, we walked all evening in sleet, hail, and thunderstorms, but managed to camp just below the snow line. The following morning, the peaks were blanketed in snow and we marveled at how the golden hour sunshine lit up the glistening aspen leaves.

After our quick stop at the Twin Lakes store, we headed right back out and up Hope Pass, where it was snowing lightly. We decided the drier snow was a huge improvement over the cold rain. It snowed on us again at dinnertime, where we camped next to Lake Ann (~11,800ft) and again the next morning as we headed toward Cottonwood Pass.

The view from Hope Pass

Lake Ann, Colorado

Climbing up toward Lake Ann Pass

Emerging through the clouds on Lake Ann Pass. The Lake Ann side was blanketed in thick fog, but the view toward Cottonwood Pass was perfectly clear as we reached the pass at dawn.

As we climbed up to the pass, a big black dog came bounding toward us. Trout! Our friend Jess followed and brought us to her truck where she pulled out a pan of freshly baked cinnamon rolls, a container of pasta salad, and a perfectly ripe peach. Heaven! We headed to Crested Butte to get one night in a warm, dry bed before charging on southward and up into even higher terrain.

Jonathan, Sean, Jess, and Molly at Cottonwood Pass near Crested Butte, Colorado

Leaving Cottonwood Pass the next afternoon, we managed to coordinate a meetup with the one and only Daniel Beerman aka Soapbox aka the third Captain of Us!!! Our bestie was on a two week solo adventure, heading north on the Colorado Trail, which happens to overlap the CDT for most of central Colorado. This was a very, very special moment for us both. Dan is the only person in the world who had an invite to come and hike the CDT alongside us (yeah I know, you're all clamoring to be out here getting hailed on with us). He was Jonathan's PCT hiking partner. He and his spouse, Jo, have been our home base and gear hub while on the trail. We were so incredibly excited to see him and hear about his trip! We all sat on the side of the trail swapping tales and snacks. It was a mighty fine way to spend an afternoon before we hugged goodbye and headed our respective ways.

The captains reunite!! Pedi, Frizz, and Soapbox out on the trail ❤️

As we headed toward the northern stretches of the San Juans, we suddenly hit the "bubble" (what hikers call the largest group of people along the trail). After seeing zero thruhikers on trail for days at a time, we ran into six hikers on the day before Monarch: Panty Pirate, Steamy, Casper, Radio, Charcuterie, and Stew. A couple days later, we camped with Ohm Boy and realized we hadn't had camp dinner with anyone else since Yellowstone. This was a good sign for us. We were about to head into the biggest, gnarliest mountains in Colorado and it felt nice that we just might not be out there completely on our own.

A Wet September

Storms in the high country of Colorado are no joke. We had hoped to avoid them, but the forces of nature had other plans for us.

In Colorado, September is usually lovely. The sun shines just about every day with bluebird skies and a cool breeze (hello, state with 300 plus days of sunshine per year!). The afternoon storms, common from May through July, have usually faded away, making September the best time to be in the alpine. Usually. We arrived in Colorado on September 6th. Great timing!

What September in Colorado is supposed to look like

The first day out of Steamboat was idyllic, possibly the most scenic paved road walk we'd ever done, followed by miles of dirt road lined with glowing golden aspens. The sky turned itself the deepest imaginable blue as we climbed up toward Poison Ridge. We camped high on the ridge with a glorious view.

We were headed to the Neversummer range and then on to Rocky Mountain National Park and the Indian Peaks Wilderness. This is all terrain we've played in for a decade. We know these trails, we know the big loops and hidden gems, but we've never connected them all together. So, the next morning, when we caught a gorgeous, glowing, apricot sky at dawn, we were thrilled to be exactly where we were.

Those rosy fingers of dawn near Poison Ridge

The weather started to turn soon after dawn. There were storm clouds gathering around us in every direction as we skirted around some lower peaks, but nothing quite seemed to be moving in our direction. We kept one eye on them for the morning, feeling safe under the cover of the forest with little more than a light sprinkle of rain. Top of mind for us was the summit of Parkview Mountain, our first point on trail above 12k feet and also home to the steepest mile on the CDT.

Above treeline, the weather becomes a critical factor in how we make decisions on trail. Being wet and cold in any terrain can make things miserable, especially wet weather that continues day after day. But above treeline, exposed to high winds and lightning, it becomes dangerous. Storms in the mountains can be incredibly unpredictable and in Colorado, we spend a whole lot more time way, way above treeline.

Molly hiking above treeline with storm clouds gathering behind her

Making decisions around weather as a thruhiker is also a little different than when you're just doing a day hike. When you're just out for the day, you can choose your window, choose your location, choose your weather. You can stay home if things aren't looking great. In order to complete a full thru-hike, you simply can't wait out every storm. You can't wait your way to Mexico! There's a dual pressure that's weighing against over-caution: the season isn't all that long and we only carry so many supplies at a time. We might not have enough food to add a day to our itinerary at any given time. Waiting too long can also backfire. Sometimes, the weather ends up coming in later than expected and a mediocre window turns into a no-go situation.

As we climbed above treeline, heading toward Parkview, the wind was so loud that we had to yell to be heard, even hiking 10 feet apart. We waited for a bit at the last little clusters of krummholz, trying to judge whether any of the storms were heading our way. The wind direction seemed to be in our favor. There's also a small shelter on top of Parkview (basically a plywood shack with a lightning rod). With only one mile to the shelter, we decided that we had enough of a window to make it to the top, where we could duck in and then make a decision on when to descend.

Looking back down the ridgeline of Parkview Mountain

Moody skies behind the ridge of Parkview (left)

One mile is a quick jaunt. One mile is measured in minutes. One mile is nothing. But one mile with 1100 feet of ascent on near-vertical grass-wall at 12k feet does not feel like nothing when you're 20 miles into your day, have already climbed more than 5000 feet, and you're in a race against the sky. Just few hundred feet up the climb, thunder began to boom a few miles off. The wind was trying its damnedest to blow us right off the mountain, and was pushing us back down with every hard-earned step. I definitely hit my physical limit, then blew right on past it, hiking as fast as I could to try to beat the storm.

I laughed with joy and relief as we came over a ridge and watched the storm move on past. But by the time we got to the shelter, we were both cooked. I put on every layer I owned and sat on the wood floor of the shelter, leaning against my pack and staring into the void, blindly gobbling up as many calories as I could manage with my frozen fingers. The thunder still rumbled nearby, but the storm had indeed missed us by a few miles, as we'd hoped. After a few moments of rest, we peered out of our wind shelter and determined that we needed to get back down below treeline before the window was lost.

Jonathan already well above treeline with peaks still rising hundreds of feet above

After Parkview, we climbed up and over the Neversummers and headed into Rocky Mountain National Park. It rained a little bit each day between Parkview and the town of Grand Lake, and morale was already a little damp. We were able to dry things out most days, but all of our gear was starting to get a coating of mud and mildew.

Leaving Grand Lake, we woke up to a steady rain. It was misty as we walked along the Colorado River, fresh from its headwaters on the west side of the Park. That night, it stormed again, huge thunderclaps above us as we headed for camp. The nighttime temperatures had been dropping rapidly and it was freezing cold when we got into the tent. When we woke up, it was 40 degrees and still raining lightly. Neither of us was thrilled to get out of bed, so we "slept in" until around 5:30am and ate breakfast (OK, Snickers bars) in our sleeping bags. We started walking while it was still dark and got used to the drizzle until we started to climb and that drizzle began turning to snow.

A misty morning along the Colorado River

Another thing to know about these weather decisions: there are times when the decision is about grit. About how much you can handle. And then there are times when you either have the resources or you don't. Times when carrying on is a matter of courage and times when it's a matter of wisdom. That line can be narrow, but judging it correctly can save your life.

Rain turns to snow as we climb up toward the Continental Divide

In flurries of snow, we continued to climb up past the last of the trees toward the divide and toward a very familiar trail. The High Lonesome Trail is part of a loop we've each run a half dozen times or more. But the snow was increasing and the wind was getting intense. Visibility was maybe around 40 feet. The day prior, Jonathan had lost his gloves, so by this point, he was using Molly's socks to keep his hands from freezing. Molly's sleeping pad had also sprung a leak, and the night before, she'd woken up several times to keep from sleeping on the ground. The wind was gusting 30 miles per hour and sandblasting us with ice from the west.

Rime coats the CDT trail marker on the Divide along the High Lonesome loop

We checked in, but carried on for a couple of miles, knowing that we'd have some options for a bail point down toward Boulder to the east or toward Winter Park to the west. From the point where we hit the Divide, the trail stays above 12k feet for several miles before heading even higher up toward James Peak at 13,271ft. So, when we reached the junction for King Lake, we ducked below the ridge to deliberate on the best way forward. We knew we couldn't camp up that high in those conditions, and that our warmer gear was waiting for us in the Front Range (to the east). The winter found us just a little too soon. So, we bailed. We headed down toward King Lake and then six more miles down to the Hessie Trailhead, which is about a 45 minute drive from our home in Boulder. With cell phone service just below the Divide, we made some calls and connected with our friend's dad, Phil, who generously agreed to come scoop us up from the trailhead. A few hours later, we were eating poké in a suburb of Denver where it was 76⁰ and sunny. Ah, mountain weather.

Up for the adventure, Phil kindly agreed to drive us back out the next day to finish out the section we'd planned to complete. The weather was clear and sunny when we hiked north from Berthoud Pass, equiped with new gloves, a new sleeping pad, and several additional warm layers. The snow was gone, except for a few small patches lingering in the deepest shade. In the bright sunshine, we opted for a ridgeline alternate that summited five 13k foot peaks, finally descending from James Peak to the same junction where we'd bailed the previous day. It was unrecognizable. We could see the Denver skyline, not to mention King Lake, which -- though it's right next to the trail -- we hadn't had a glimpse of the day before. What a difference one day can make.

Perfectly clear skies and stunning views, one day later

Permanent snow fields along the ridge, with no trace of the snow from the day before

Molly descends from Mt. Bancroft, heading toward James Peak

Molly walks the Divide back to the junction where we'd bailed the day prior. Snow?! What snow?!

King Lake, Indian Peaks Wilderness

This September has been unseasonably wet and abnormally cold. Later on, after many days of rain and hail, I'd eventually make up several verses of a new hit song called A Wet September, to the tune of A Long December by the Counting Crows. Maybe we were starting to lose it, just a little… In spite of the rain though, we've still seen some incredible views and we're excited for what central and southern Colorado will bring. Bring it on, September!

Homecoming

For most of Wyoming we were daydreaming about making it back to Colorado. Finally, we made those dreams a reality. It brought on some big feelings.

Early in the morning of our last full day in Wyoming, we finally walked back into a small, but dense patch of forest. Birds flitted around the branches above us, flowers still lingered below, and the trail was soft and lightly spongy under our sore feet. We paused to breathe in the damp air of that deep, shady, green place.

All morning, we wove up and down gently rolling hills, mostly still covered in scraggly sagebrush, but every so often plunging into pines, spruces, or airy aspen stands. As we climbed slowly higher, the air behind us grew thick and smoky, but this time, we were walking away from it. For the first time in weeks, another hiker caught up to us and walked with us for half a day or so. Du Jour had been just behind us since the Tetons, he told us. He'd been caught up in the chaos of the Dollar Lake Fire too and had also gotten wind, rain, and hail in the Wind Rivers. The miles sped by as we chatted about anything and everything, happy to have a friend to walk with for a while.

Midday, we crossed a highway where Du Jour left us to head into Saratoga for the night. We carried on into the Huston Park Wilderness where — while we sat eating a late lunch by a clear, rushing creek — two other hikers passed by. A crowd! We rejoiced in the quiet, cow-free beauty of the wilderness, camping in a stand of tall trees on the edge of a huge open meadow that was starting to look just a bit like Colorado.

The next morning, we finally climbed back up into the alpine for the first time in a week. The steep, rocky trail was punishing after so many flat miles, but we both were overwhelmed with joy to be back in the mountains again. It turns out, we do still love to hike!

That afternoon, we hit our 1500 mile marker, where we drew the number in the dirt, and held a little celebration (pretty much a high five and some extra gummy bears). We made it halfway from Canada to Mexico!! (You might be thinking: "They only JUST made it HALF of the way?!" We were thinking: "We're going to do that AGAIN?!").

Shortly after our halfway point, we met up with Frito and walked with him for while as we approached our second big milestone of the day: the Colorado border! Two license plates and little rock signs designated the state line on the trail. We sat for a moment to eat lunch and celebrate returning home.

Our home state is a rugged one and the CDT doesn't shy away from high elevation or to the exposed, rocky terrain. After some trail rutted from dirt bike tires and a stretch of ATV track crowded with bow hunters, we reached the Wilderness and the base of our first massive climb from 8,000ft to 11,800ft over the course of around 10 miles. The trail was beautiful, switch backing up a rocky ridge with peekaboo views out to 13k foot peaks and rich, green valleys where the willows were beginning to turn their autumn ochre. Up, up, up we went; it felt so good to have a goal, to stay focused on moving upward, knowing we needed to get up and over before nightfall.

We met a deer hunter, packing out the last of his gear. It was his third trip up the drainage after packing out all of the meat, which would feed him and his family for months to come. We have learned a lot about hunters out here, chatting with the folks we meet, exchanging questions about our very different sports. We see the hunters at all hours, in places few other hikers ever reach. Seeing the destruction wreaked by cattle across the northern states, there's a certain appeal to their quest. After all, there's unlikely to be a more sustainable meat than deer you've hunted on foot and processed in your own garage (like our friend with the deer was planning to do).

Then we made it to the final push. Some clouds threatened behind us, but as we crested the top of Lost Ranger Peak, the sky was clear and the views were jaw-dropping. All around gorgeous alpine lakes and forests studded stark rocky peaks, but our eyes were focused on the eastern horizon where, way off in the distance, we got our first glimpse of Longs Peak from the CDT. Longs Peak is a 14,255ft peak in Rocky Mountain National Park that we've both climbed multiple times. More than that though, it represents our home terrain, a peak we've seen from the east side hundreds of times. We're really here!!

The Great Divide Basin

A section most noteworthy for being flat and hot may not sound like the most alluring blog fodder, but this section was quite an interesting one.

Wyoming’s Great Divide Basin was undeniably the weirdest part of the CDT so far. The Continental Divide splits around this huge, flat desert, leaving a wide endorheic basin surrounded by the two ridges of the Divide to the east and west. endorheic means that any rainwater falling into the basin drains only into that basin’s own interior, not to any external river or ocean. The Great Divide Basin sits at a much lower average elevation than the trail to the north and south, it has no real mountains to speak of, and it is just a completely open expanse. There is no one there – in the whole basin, there is only one incorporated town, population 203 as of 2020.

Hikers mostly use the flat terrain of the Basin to get through a lot of miles as quickly as possible. We were a bit behind schedule after leaving the Winds, so we fully embraced the idea of pushing through some extra miles to get us back on track. On our first full day, we hiked 31 miles with only 2077 feet of elevation gain. To put that in perspective, on our first full day in the Winds, we covered just over 20 miles with almost 5000 feet of gain; that's nearly four times as much gain per mile. On our second day, we decided to go a little bigger.

We’d already been walking for almost an hour when the first rays of light spilled over the horizon, revealing a herd of antelope along the crest of the ridge above us in silhouette. As the sun rose, we watched them run along the ridgeline like a scene from National Geographic.

After the stunning sunrise, the view settled into a slowly undulating sea of sagebrush and sand. The arrow-straight, unchanging trail made us appreciate how much our hiking brains rely on the endlessly diverse forests and mountain landscapes. This perpetual sameness makes the Basin a mental challenge as much as a physical one. We both plugged in our headphones and listened to podcasts for a few hours to give our brains some stimulation as our feet moved us forward.

The heat became intense and our chrome-topped umbrellas became a vital resource to help us stay cool. We rigged them to our backpacks and carried on, slightly more protected from the glaring sun, and reminisced about the lovely shade of trees.

Though we encountered very, very few people in the Basin, huge swaths of the land are used for grazing cattle, which takes a massive toll on the land. The cows churn up the soil, decimate the vegetation, and turn every spring, creek, and pond into a shit-filled mudhole. Lovely. As part of the Red Desert, the Basin gets just 7-10 inches of rain each year on average. Water is an extremely limited resource. For hikers, this means carrying water for miles and sometimes venturing off trail to find even remotely reasonable water sources to pull from.

This lake may look pretty from a distance, but don't let it fool you. It's a giant pool of stagnant water and the second worst water source we had to pull from.

Don't let this one fool you either. It's just a dry bed of salt and dirt.

The ground was so dry it crackled and crunched underfoot.

During some of the year, local groups fill up water caches along the dirt roads, leaving gallon jugs of clean water for hikers to fill up. But we had arrived too late. Every water cache we came to was empty, leaving us to make do with what was available. Midday, we were forced to fill up at a large pond surrounded by cow pies. As I inspected the water, a hawk dove down toward the pond to harass some ducks feeding in the weeds along the far side of the pond. The water was slightly murky and full of… life. There were small, round organisms flitting around with long tentacle-like appendages and little bugs cruising along the muddy bottom. I gagged a little as I bent down to fill our dirty water bag. The next water source was over 20 miles down the trail, so we fortified ourselves and collected what we needed. We carry both a ceramic Sawyer filter and also water treatment tablets, so we double-treated the water, then added flavoring to cover up any lingering taste issues.

Molly scoops water into the CNOC bag where we store dirty water before squeezing it through our filter. This might be the worst water on the whole CDT.

As the afternoon of that second day wore on, we climbed over some low ridges, mostly on two track gravel roads. Mile after mile after mile, the trail rolled along straight through the sagebrush. We ate dinner just before the sun set, in the company of two suspicious mama cows and their admittedly adorable calves. Then we put on our headlamps and walked on into the dusk.

When it was too dark to see our feet, we turned on the headlamps and kept on rolling. Coyotes began howling and yipping somewhere in the darkness and the howls were answered from the other side of the trail. I got spooked at some eyes glowing back at me down the trail — a coyote? A mountain lion? A wolf?! Nope, just a cow.

We heard some chirping from close by and spotted a common poorwill crouched under a sage bush. Then suddenly something swooped over our heads. We looked up and put headlamps illuminated a snowy owl circling just a few feet overhead. It circled around us again, then dropped to eye level to examine us, pumped its wide wings twice to steady itself in the air, then soared away in complete silence

A curious antelope

It was 10:45pm or so when we finally set up the tent having successfully completed a 40 mile day.